The Book of Erections

The Penis: A User’s Guide

Everything you ever needed to know about erections and how they work, why they sometimes don’t, and what to do to keep them healthy.

Chapter 1: The Anatomy of an Erection

Think of a penis like a balloon.

When it’s empty, it’s unstructured and floppy. If you fill it with water, it becomes firm and gains structure as the walls stretch and widen out. Here the similarities end. A penis will not burst or float away, and it is rarely a welcome addition to a party.

A penis, contrary to popular belief, is not a muscle, although it does contain a unique muscular structure which plays a key role in the process leading to an erection.

In this chapter we will examine the anatomy and physiology of an erection in detail and why, when it comes to getting hard, it pays to be relaxed.

An erection is like a reflex: an unconscious reaction to a gentle touch, a sweet nothing in your ear, an erotic image on your laptop or the power of your imagination...

The muscular tissue in the penis is truly unique, specialised to fill with blood in response to an involuntary pathway, essentially an unconscious action like a reflex. This can be activated by:

- Touch

- Audio Prompts

- Visual Prompts

- Fantasy

Erections happen as a result of relaxation of the arteries and the spongy, muscular tissue in the penis. As these open up, the penis fills with blood which gets trapped there, and it thereby becomes hard.

Compare this to the muscles we can use at will, such as flexing a bicep or giving someone the finger when they cut you up in traffic. An erection has more in common with a reflex, an involuntary response, which makes it much harder to control or rely on.

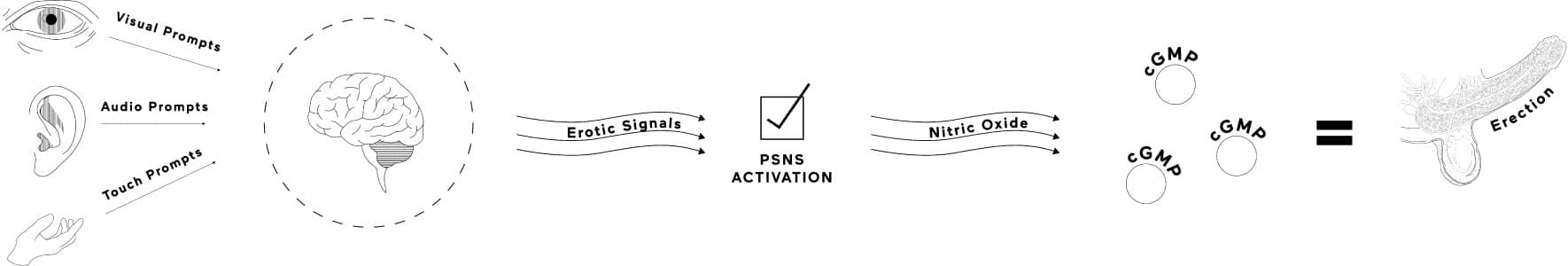

When this process is triggered, a signalling molecule called cGMP is synthesised. It is this molecule which signals to the muscular tissue in the penis to relax and fill with blood, and an erection — whether you wanted one or not — to materialise.

An enzyme called PDE5 is normally around to break it down and, as a result, your erection subsides. Now for the clever bit: medication such as Sildenafil (Viagra) and Tadalafil (Cialis) block this enzymatic reaction - leaving more cGMP intact - making for a harder, longer-lasting erection. These medications are known as PDE5 inhibitors.

Let’s look at a diagram to understand this process better...

PSNS = Parasympathetic Nervous System

Like a good three-piece band, all players need to be working well and in unity. A drunk drummer or absent bassist can spoil the show. Or, in this context, your bedroom performance may be below your usual standards, or your erection may not turn up at all.

For healthy erectile function all three of these systems — nervous, cardiovascular and the penis itself — must be working effectively and in glorious unity.

In order to understand how things can go wrong, it’s best first to understand what these systems do when they’re ticking along smoothly.

Three main systems in the body need to coordinate for an erection to happen...

- Nervous system

- Cardiovascular system

- Structures within the penis itself

The nervous system: sending the signals

The nervous system has a big job: to transmit and translate information between different parts of the body, processing information on pain, temperature, balance and much more. When you get into a bath that’s too hot, you can thank it for helping you jump out before anything gets cooked or scalded.

It also processes and coordinates erotic stimuli: the touch of a hand, the sweet words of your lover, a complex fantasy involving a nun and a fireman, and the involuntary process which leads to erection.

The nervous system communicates via electrochemical signals which are carried along specialised cells called neurons. These are relatively quick in comparison to other signalling systems within the body such as hormones - this is why an erection can arrive rapidly should something adequately float your boat.

The nervous system is divided into two parts:

- Central — The brain and the spinal cord

- Peripheral — The nerves which carry information to and from the brain and spinal cord

The peripheral nervous system: keeping you connected (...internally)

When an erection arrives without you necessarily wanting one, you have the peripheral nervous system (PNS) to thank. When it struggles to arrive at all, the finger points to its sympathetic subsystem...

The PNS refers to all of the nerves outside of the brain and spinal cord, penetrating internal organs, skin and muscles. It relays information such as touch, balance and temperature to the central nervous system, where it is then processed and made conscious. The PNS is divided into the somatic and autonomic nervous systems; the latter is highly involved in how your erection functions.

Heart rate and digestion, and reflex actions such as sneezing, coughing and vomiting, are all processes which require no conscious control. These all rely on the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which also happens to be the neurological manager of erections.

The ANS is further subdivided into the sympathetic (SNS) and parasympathetic nervous systems (PSNS). These stimulate complementary sets of reactions within the body. They operate in a balance — as one becomes more active, the other is suppressed and vice versa.

The sympathetic nervous system: stopping erections in their tracks since, well, forever

When the body is under stress or senses danger, the SNS is activated. Heart rate is increased, airways within the lungs are dilated, sweat is secreted, the pupil of the eye dilates (to enhance distant vision), blood supply to the muscles is increased and less blood is supplied to all organs not necessary to your immediate survival — including the penis.

Key takeaway

Anxiety and stress creates a ‘fight or flight’ response. The result? Less blood is supplied to organs not necessary for your immediate survival — that includes your penis.

The net effect of these actions, popularly known as ‘fight or flight’ responses, is to prepare the body for action. Sex, unfortunately, is not one such action.

This was evolutionarily beneficial when our day-to-day existence largely involved running from predators but as modern human beings, these responses can be unwelcome and triggered at inopportune moments.

Perhaps you’ve been trying to charm someone for months when you finally succeed. The lights are turned low, you’re excited, you’re ready — then this evolutionary hard-wiring kicks in. Your first-night nerves are wrongly interpreted as being chased by a hungry alligator. And nobody needs an erection with a 230-kilo reptile bearing down on them. The result? Your erection slowly peters away.

The parasympathetic nervous system: the hero behind every welcome erection.

The PSNS, in contrast to the SNS, is activated when the body feels relaxed. Whether this calm state is achieved through meditation or with the help of a ‘Slow Bedroom Jamz’ playlist, the effects are the same: heart rate is slowed, salivation and digestion stimulated, along with sexual arousal.

In men, activation of the PSNS stimulates the arteries and muscular structures in the penis to dilate (open), encouraging blood to flow into it and preventing blood from leaving, which causes your penis to become hard. In women, there is similar dilatation of arteries in the clitoris, causing relatively subtler engorgement and enhancing sensitivity.

Collectively these are sometimes known as ‘rest and digest’ or ‘feed and breed’ responses (which, as it happens, would make equally good Spotify playlist titles).

In contrast, stimulation of the SNS reduces blood supply to the penis and inhibits the erectile response. Or to bring it to its climatic ending: ejaculation.

Interestingly, nocturnal erections are thought to occur because of inhibition of the SNS during REM (rapid eye movement) sleep, which results in relative activation of the PSNS.

Depending on how stressed the mind and body is feeling, sexual arousal can be promoted or blocked by autonomic nervous system (ANS).

The somatic nervous system: the bit you can control

But what about the things you are aware of, or that you can control? Sensations of touch and taste, and the voluntary movement of muscles are the responsibility of the somatic nervous system, the other division of the PNS.

Direct tactile stimulation of the genital organs — be that by a consenting friend or of your own doing — results in signals being sent to the central nervous system (causing conscious perception of this stimuli) and activation of the PSNS, inducing an erection.

The central nervous system: the mainframe

Enclosed within the skull and spine are the brain and spinal cord, respectively. These make up the CNS; the system which coordinates and processes every touch, sensation and stimulus received by the peripheral nervous system, and transforms it into conscious perception.

The brain can initiate an erection in response to audiovisual stimuli, such as seeing a sexy firefighter emerging from a smouldering building, or fantasy, imagining you’re being carried by said firefighter. Signals are sent, via the spinal cord, to activate the autonomic pathways with the end result, an erection.

The nervous system and the penis: a summary There are three ways that the nervous system can be activated to trigger an erection:

-

The brain —

stimulated by sound, sight or fantasy, the brain can send signals via the spinal cord to activate the PSNS. -

Touch —

the somatic nervous system transmits signals from touch sensors in the genital region to the brain, resulting in the conscious perception of touch, and PSNS, activating the erectile response. -

Suppression of the SNS —

when you’re asleep, your body is relaxed and the SNS is more quiet. This is thought to result in relative activation of the PSNS, which is why you wake up with an erection in your pyjamas.

The cardiovascular system getting the blood to where it’s needed most

The symbolic connection between love and the heart go back, it’s thought, as far as the first century AD. The relationship between the penis and the heart is much less celebrated or likely to appear on Valentine’s cards, but it’s a hard, physiological fact.

The cardiovascular system is composed of the heart and all of the veins and arteries in the body. Its function is to circulate substances necessary to sustain life, including oxygen and carbon dioxide, sugar, electrolytes, cells which fight infection and hormones.

It might be easier to conceptualise it as the plumbing system of the body — the heart is essentially a pump, which needs to function efficiently in order to ensure appropriate blood pressure.

The pipes of the body are the arteries and veins, which should be smooth, unobstructed and straight as possible in order to allow uninterrupted, streamlined blood flow. Arteries carry oxygen-rich blood from the heart to the organs, muscles and tissues, and veins carry the blood back to the heart, and from there, back to the lungs to resupply it with oxygen.

When activated, the PSNS triggers dilatation of arteries in the penis, allowing blood to flow in. A strong, firm, erection depends on these arteries being healthy — we’ll cover the problems that can arise here in later chapters.

The penis where everything comes perfectly together

Motionless and flaccid: for most of the day, your penis hangs there doing very little at all. But when prompted, provided the heart is pumping efficiently, the arteries are healthy and the nervous system is operating smoothly, it is ready to spring into action like a highly-caffeinated doctor on-call.

In response to a parasympathetic activation (the reflex that tells your penis when it’s time for business), blood enters the sinusoids of the corpus cavernosum, a unique, spongy, muscular tissue which spans the length of the penis, allowing it to become erect.

If the timing and place is right (in bed with your consenting partner, right, on a bus, not so right), sex or masturbation may swiftly ensue, followed by ejaculation.

This climactic finish stimulates the SNS, resulting in constriction of the arteries and allowing the blood that had been trapped to flow back through the veins. The penis once again becomes flaccid.

Now you know how an erection works.

When it isn’t working, this is how medication can make it more reliable...

There is smooth muscular tissue within the walls of arteries which allow them to widen and narrow. The spongy tissue of the corpus cavernosum of the penis responds similarly.

When triggered by the PSNS, molecular signals result in the relaxation of the walls of the arteries and the corpus cavernosum, encouraging blood flow into the penis, and an erection to proudly present itself.

During this process, cells which line the arteries and muscles release nitric oxide, which starts a cascade of signals within the muscle cells. One of the most important messengers here is cGMP, a molecule which instructs the muscle proteins to relax.

For an erection to subside — whether that’s desired or not — cGMP needs to be broken down by an enzyme called PDE5. Stopping, or inhibiting, this enzyme before it gets to work, keeps the cGMP intact, the smooth muscles relaxed, and your erection very much there.

This is how the entire class of PDE5 inhibiting medications work — including Sildenafil and Tadalafil (Cialis). They block the breakdown of cGMP, so that blood remains trapped in your penis, and your erection is maintained for the task at hand, be that making slow, passionate love or a five-and-a-half-minute session on a Tuesday night.

Once you understand how muscles relax and arteries dilate in an erection, it’s easier to get to grips with how medication for erectile dysfunction — such as Sildenafil — works

The endocrine system where testosterone comes into play

The endocrine system consists of a network of organs which regulate the release of hormones into the bloodstream. One of these hormones has become synonymous with all things male, hairy and aggressive: testosterone.

Largely produced in the testicles — and contrary to its often bad press — it promotes healthy sperm production, libido, bone and muscle strength. While low levels can cause erectile dysfunction, it’s still not known exactly why.

A number of different theories have been suggested as to how testosterone is involved in healthy erectile function. Some of the suggested roles include:

- — involvement in healthy growth and functioning of the nerves involved in erection

- — involvement in production of nitric oxide, and thus the activity of PDE5

As research into the roles of testosterone in erectile function grows, new treatment strategies may emerge. But until that time, PDE5 inhibitors remain the prime means to treat the symptoms of erectile dysfunction — and effectively at that.

The cardiovascular and nervous systems may take the limelight in the average biology textbook, but the endocrine system has more than just a supporting role in a healthy, fully-functioning body, and that goes for healthy erectile function too.

Exactly what this role is remains somewhat of a mystery.

So now you know: an erection is a truly remarkable piece of physiological engineering. An intricate sequence of events, one with numerous stages, and complex systems required to work in perfect harmony.

Of course, with so much going on, and everything so finely balanced, there is potentially more that could go wrong. In the next chapters we’ll explore some of the different reasons why erections can become elusive, and the different ways you can make them more reliable.

References

Dean, R. and Lue, T. (2005). Physiology of Penile Erection and Pathophysiology of Erectile Dysfunction. Urologic Clinics of North America, 32(4), pp.379-395.

Traish, A., Goldstein, I. and Kim, N. (2007). Testosterone and Erectile Function: From Basic Research to a New Clinical Paradigm for Managing Men with Androgen Insufficiency and Erectile Dysfunction. European Urology, 52(1), pp.54-70.

Author:

Dr Saskia Verhagen

MRCP(UK) MBBS BSc (Hons.)

Editor:

Mr Joe Barnes

Numan Editor

Medical Advice Disclaimer

All of the content in this Book is to be considered general information and not intended to amount to medical advice. If you are seeking medical advice, you should contact a doctor or clinician and refrain from taking any action regarding your health based on the content of this Book. All product information is for educational purposes and we make no assurances or guarantees as to its completeness, accuracy or whether it is up to date.